For the last two centuries – a recent period in terms of musical history – western musicians have been using imperfect musical intervals: those of the equal temperament with 12 notes per octave. Although these intervals have been used to compose thoughout many different types of music, in reality they are merely the result of a mathematical compromise to simplify the development of a certain category of acoustic and later electronic instruments, and they do not take into account the finesse of our system of perception.

A number of studies have demonstrated that we have a much greater analytical capacity than simply being able to recognise 12 tempered intervals; we are also capable of integrating a significant amount of psycho-sensory factors, including tone and intonation.

Historically, in the 17th century, the philosopher and mathematician Leibniz set forth the theory of “subconscious evaluation” according to which music is defined “as the pleasure of the soul which counts and which does not know it counts”.

The Pythagorian musical theorist Jean-Philippe Rameau followed this idea when he established a connection between our perception of musical intervals and mathematics, and affirmed that melody arises from harmony, and through it “is able to perceive the relationships between numbers, as they arise throught the universe”.

More recently, a number of composers, including Harry Partch, Lou Harrison, Terry Riley, La Monte Young, Ben Johnston, Wendy Carlos, David B. Doty, and Robert Rich have used various microtonal scales, reconnecting with traditional music throughout the world, or creating new temperaments or scales, according to just intonation.

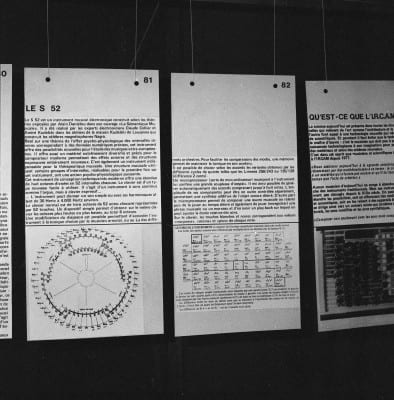

With a similar approach to Leibniz or Rameau, Alain Daniélou was highly committed to the study of musical intervals, after having studied Indan music and its subtleties for a good part of his life. He elaborated a musical scale of 53 notes, exclusively built of ratios of numbers 2, 3 and 5, and theory which, according to Fritz Winckel, “allows musical ratios to appear in a whole new light” (as described in his work “Sémantique Musicale”).

In his teens, Alain Daniélou was already seeking to build an instrument with micro-intervals. The Semantic Daniélou, in its physical version (36 notes) and its software version (53 notes), is the result of almost 70 years of work and is a remarkable demonstration of perserverence. In both versions, the instrument respects the theory of the three number combination Daniélou set forth, with the Semantic Daniélou-53 offering the total possible harmonic combinations of the Semantic system.

Jacques Dudon

Jacques Cloarec retraces the key milestones of the project.

From a very young age, Alain Daniélou showed a great interest for artistic pursuits. He painted (water colours), and continued to do so throughout his whole life, he sang, and he learned to play the piano. Later, he studied composition with Mal d’Olonne, encountered the world of dance and gave recitals.

In 1926, he was 19 years old. He received a grant for a trip to Algeria to study Arab music. I believe that it was during this period that he became aware of the limits, and to a certain degree the abberation of the musical system which divides an octave into 12 equal semitones, a concept which prevents musicians interpreting Arab music or in fact most kinds, other than western music. He thus took up the torch after his illustrious predecessors: Zarlino, Werckmeister, Mercator, Holder, Helmholtz, etc.

Holder and Mercator divided the octave into 53 equal parts; an approach which has similarities with the system conceived by Alain Daniélou, but which did not, as Daniélou’s did, preserve the naural tuning of intervals created by the harmonics 3 and 5, illustrated used by the Indian shrutis.

I could not confirm it, yet I suspect that the idea of a new musical instrument did not being to dawn in his mind during his trip to Algeria in 1926.

His discovery of Indian music a few years later reinforced his passion for this research.

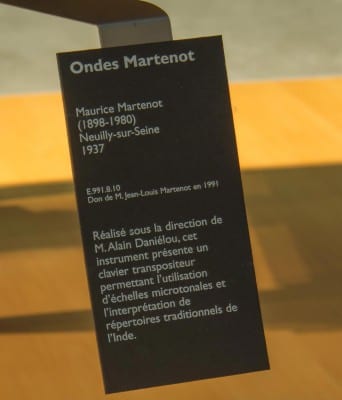

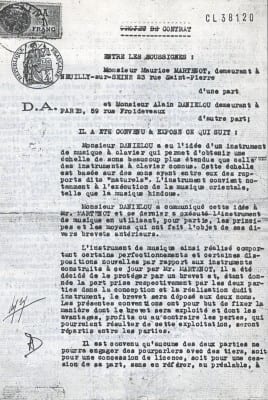

In 1936, he worked in partnership with Maurice Martenot to develop the first instrument with a tuneable keyboard: I still have the draft contract and the patent of 1937 which the musicians filed, and I have donated to the “Association pour la Promotion et la Diffusion des Ondes Martenot” (Organisation for the Promotion and Broadcasting of Ondes Martenot) the prototype which was created at the time. I recently rediscovered it at the Musée de la Musique de La Villette à Paris (Paris La Villette Music Museum)

A few years later, Alain Daniélou developed a new hand-crafted instrument in India, whose design included a large quantity of bicycle spokes. He then had a series of small harmoniums made, called Shruti Veena, of which one remains.

Inner Traditions International (1995)

His first book, naturally dedicated to the same subject; “An Introduction to the Study of Musical Scales”, was published in 1943 in London (by an Indian company). It was later translated into a French version with the title “Traité de Musicologie Comparée” (Treatise on Comparative Musicology) and a new American version was published in 1995; “Music and the Power of Sound », with an introduction by Sylvano Bussotti. The final version on the same subject; “Sémantique Musicale”, was published in Paris in 1967 and has since been regularly reprinted with different introductions (Fritz Winckel, acoustician and Françoise Escal, musicologist). The latest version, revised and prefaced by Jacques Dudon and related to the new instrument, is currently being printed (also scheduled to be launched in e-book format and in English). These books bear witness to the ongoing interest of musicians, musicologists, psychologists and acousticians for the research of Alain Daniélou.

The project of building a precise instrument began again in 1970’s, when Alain Daniélou decided to develop a une instrument using the latest electronic technology, with his friend the engineer Stefan Kudelski, known for inventing and building the Nagra, a luxury portable tape-recorder.

Stefan Kudelski passed the project on to his son André, a young electronics engineer, and Claude Cellier, an electronics engineer and musician.

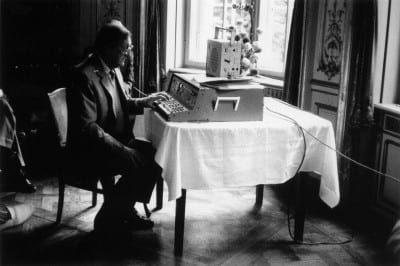

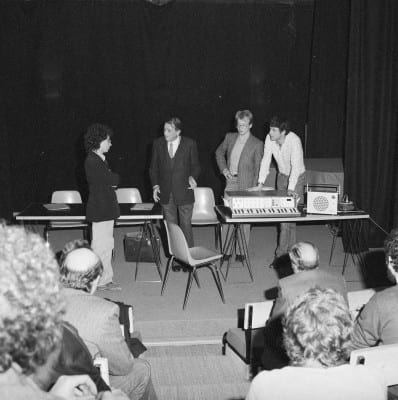

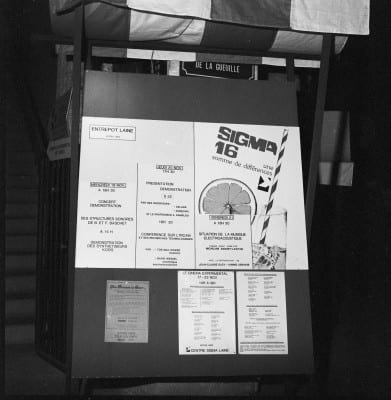

This new instrument, named the S52, which was based exactly on the system described in the book “Sémantique Musicale” and was technically very elaborated, did present a few shortcomings, but nevertheless enabled Alain Daniélou to advance with his theory inspired from the Indian model, and to test its psychoacoustic applications. The prototype was presented in Paris in 1980, amongst others to the UNESCO International Music Council as well as the IRCAM (Institut de Recherche et Coordination Acoustique/Musique – Research and Acoustic/Music Coordination Institute), and afterwards in Bordeaux, Berlin, Rome, etc.

Christened as the “organ of Shiva” by the le journalist Jean Chalon, the S52 remained a prototype, since its keyboard was used more as an experimental apparatus than a real musical instrument.

Interest for such an instrument was immediate, be it amongst people working in fields concerned by micro-intervals in music, amongst music-therapy specialists or in non-european music. Sylvano Bussotti, who had until then never included electronic instruments in his works, became highly interested in the project, and wrote a piece for the instrument, which was played by the pianist Mauro Castellano and directed by the conductor Marcello Panni in a work called “La Vergine ispirata”.

Jacques Cloarec,

4th April 2005

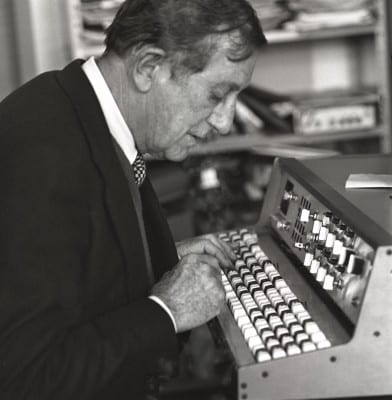

The aventure does not end here, since two years before the death of Alain Daniélou, the ethnomusicologist Xavier Bellenger brought together Michel Geiss and Jacques Cloarec. During a meeting in Lausanne, Alain Daniélou, already quite frail, informed Michel Geiss of his desire to have an instrument made based on his theory. Michel Geiss suggested that the instrument could be conceived in the form of an electronic keyboard with accordion type buttons. This type of keyboard would allow a density of notes best adapted for playing a larger number of notes per octave. Alain Daniélou validated the concept and proposed that the layout of the notes be simplified by reducing them to 36 per octave, which he judged sufficient (Handwritten letter by Alain Daniélou to Michel Geiss on the subject of the keyboard).

Follwing these guidelines, Michel Geiss called on two collaborators: Christian Braut, an computorised music specialist, and Jean-Claude Dubois, eclectronics engineer, in order to build the instrument.

Daniélou died in 1994 without having seen the outcome of the project.

Philippe Monsire, an industrial designer, was in charge of creating the futuristic shell to contain all the different elements of this new instrument. It was given its name by the composer Sylvano Bussotti, who called it the “Semantic Daniélou”. Although it was operational, this first model remained for a long time in the developmental stages, an instrument with somewhat rudimental sounds, the original concept design. It was used in a number of concerts, in Paris, Rome Venise, and at the Abbey of Thoronet.

Michel Geiss later developed a considerably improved model, enhanced by recent developments in computer technology with an integrated internal computer to control sound production. This version was released in 2013. This major technological update offers a wide variety of rich and expressive sounds as well as remarkable pitch precision (a thousandth of a hundredth).

At the same time, Christian Braut and Jacques Dudon, an uncontested specialist in microtonalities, began to work on the development of a software version of the Semantic, with 53 notes per octave, available for free download via internet.

Based on the keyboard of the Semantic Daniélou-36, Jacques Dudon designed the ideal 53-note keyboard and found a MIDI interface (the Axis-64) which was compatible with its geometry. He conceived the first tunings and mappings of the instrument and wrote the specifications of the “Semantic Daniélou-53” which Christian Braut then referred to Alain Etchart of the Univers Sons team, where Arnaud Sicard finalised the IT operating system.

After a number of tests with compatible keyboards, the Semantic Daniélou-53 is today fully operational. The diversity of pre-programmed scales, each containing several modes, which can be supported by a micro-tunable drone note, make it an accessible and highly pedagogical instrument.

Our foundation, Alain Daniélou Foundation, is in charge of the promotion of these two creations, by means for example of workshops which were hosted last year and an upcoming seminar in 2017, and in doing so honours the culmination of a project which lasted for 80 years.

PHOTOS

Maurice Martenot, Alain Daniélou, 1937

Musée de la Musique (Music Museum), La Villette (Paris)

Photos: Christian Braut

Photos: Sophie Bassouls et Jacques Cloarec

After restoration by Klaus Blasquiz, spring 2016

Photos: D. Nabokov et Jacques Cloarec